Sophia Aimen Sexton

Every year on the Fourth of July, my family and I watch in awe as glittering fireworks light up the sky. We are so lucky to be living in this great country– a place where we are free to think, speak and pursue our dreams without fear.

I know a lot of immigrants who feel the same; it’s why July Fourth holds so much meaning for us.

One of these proud Americans is my friend Ahmad Batebi. He lives in Fairfax County and is an activist, a journalist for Voice of America Farsi and a doctoral student studying cybersecurity.

Ahmad Batebi now lives in Fairfax County and works for Voice of America.

Sixteen years ago, he fled his native Iran and was admitted to the United States on humanitarian parole, a temporary immigration status granted to some immigrants for urgent humanitarian reasons. It’s why Batebi has built such a rich life here – and probably the reason he’s still alive.

Now, he says, “I’d lay down my life for this country, my home.”

Some of you may know Batebi’s story. In July 1999, while a student at the University of Tehran, he joined fellow students who were protesting the closure of a reformist newspaper called Salam.

“We were fighting censorship by the Iranian regime,” Batebi told me. “We wanted access to the internet and independent news sources.”

Then Iranian security forces raided a dormitory, killing a student. Soon, the protesters realized that the government-run news channel was lying about what happened.

“Dissent was forbidden,” Batebi explains. “So, the news wasn’t reporting on the protests or why they were happening, because they didn’t want any more people to get involved.”

In the days that followed, Batebi joined thousands of students marching in the streets and demanding the truth. At least three more people were killed during clashes with Iranian security forces, and hundreds were injured or detained. One day, Batebi was standing outside the main entrance to the university when he thought he heard a bumblebee whiz past his head. He turned, only to realize a protestor standing beside him had been shot in the shoulder.

Batebi pressed the man’s shirt to his wound as he lay on the ground and helped him find medical care. He returned to the protests, waving the bloody shirt above his head – proof that police were shooting people in the crowds. A photographer captured this image, and it ran on the cover of The Economist. Suddenly, Batebi was the face of a movement. Days later, he was arrested and sentenced to death for defacing “the face of the Islamic Republic.”

Batebi spent a nearly a decade in prison, where he endured beatings, torture and threats against his family.

“There were days I was ready to die,” he admits now. “I’d pray for death because it was favorable to what I was enduring. But God didn’t kill me.”

Perhaps it was divine intervention when Batebi became so unwell that he was taken to an outside medical facility in 2008. While there, the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan helped him flee to Iraq. Then he was offered humanitarian parole in the United States.

Batebi had grown up hearing the Iranian regime demonize America.

“Their message was, ‘They are going to kill us and destroy our lives, because they need our assets and natural resources,’” he says. So he was dumbfounded when he landed at Dulles International Airport on June 24, 2008, to find a representative from the White House waiting for him.

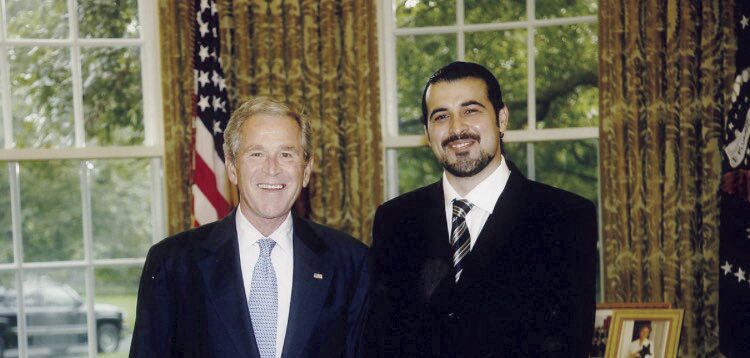

Batebi was driven to Washington, where he met then-President George W. Bush in the Oval Office. The President asked Batebi, with genuine concern, how he was doing.

“It hit me then that, a week before, I had been held prisoner, knowing I could be killed at any moment,” Batebi told me. “Now I was in the White House with the President of the United States, and he tells me, ‘Welcome home. You’re safe.’”

Batebi settled in Washington. Life wasn’t easy – he was financially dependent on his family in Iran and worked hard to improve his English. But his international profile was a major advantage. Unlike most asylum-seekers, he immediately received pro bono legal representation from a human rights organization.

Securing an attorney makes a huge difference in these cases. Most asylum-seekers lack legal representation. Conversely, among asylum-seekers who filed formal applications and had legal representation, two-thirds were approved.

Unlike so many asylum-seekers today, Batebi didn’t have to worry about being treated like a criminal or a liar. The government not only processed his claim, but did so in just one year – instead of the usual three to six years. I wish Batebi were the rule and not the exception. He and I both agree that if more Americans, and specifically American politicians, knew our stories, they would be more welcoming.

Today, Batebi says his most meaningful and fulfilling achievement – apart from being a father to his two American-born sons – is his right to practice free speech. He does this as a journalist and human rights activist.

“If I had died, I wouldn’t have the power and voice that I have today,” he says. Batebi is a phoenix, rising from the ashes. And America made that possible.

America made my life possible, too. Independence and freedom mean something very specific to both of us, because we’ve lived in societies where these human rights don’t exist. It’s why we are so thankful to have been welcomed here; many others around the world aren’t so lucky.

Sophia Aimen Sexton is a professor of English at Northern Virginia Community College’s Annandale campus and co-founder of the nonprofit Female Refugee Education Empowerment.

(2) comments

We need to read some accounts of people born in what's now the U.S. Rust Belt and journeyed to NOVA after manufacturing in the Northeast and Midwest started to collapse 50 years ago. Hint: Some are now VIPs elected to political office.

I would like this and other local and regional media to ask the region's elected under-50s (who will still be around in 2050) what the planning is and will be for a greatly increased NoVA population by 2050.

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.